LONDON (AP) — Not long ago, London was booming. Now it fears a bust.

Brexit and the coronavirus pandemic have hit Britain’s capital in a perfect storm. In 2021, the city has fewer people, fewer businesses, starker divisions and tougher choices than anyone could have expected.

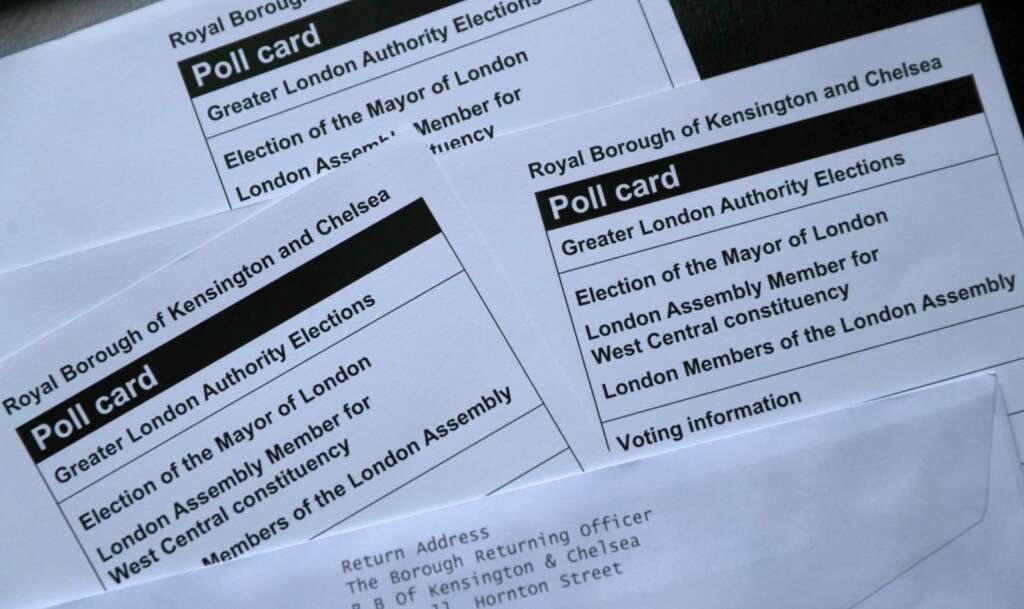

On May 6, Londoners will elect a mayor whose performance will help determine whether this is a period of decline for Europe’s biggest city — or a chance to do things better.

“It’s going to be rough, definitely,” said Jack Brown, lecturer in London studies at King’s College London. “Those two quite seismic changes” — Brexit and the virus — “will be a lot to cope with.”

___

Plagues, fires, war — London has survived them all. But it has never had a year like this. The coronavirus has killed more than 15,000 Londoners and shaken the foundations of one of the world’s great cities. As a fast-moving mass vaccination campaign holds the promise of a wider reopening, The Associated Press looks at the pandemic’s impact on London’s people and institutions and asks what the future might hold.

___

London’s newly elected mayor will lead a city of more than 8 million that is facing the usual big-city troubles — too little affordable housing and transit, too much crime and pollution — as well as a host of unprecedented problems.

A year of coronavirus lockdowns and travel restrictions have emptied the city’s office towers, shut down its nightlife, shuttered its pubs and restaurants and banished international tourists. Returning to normal will take a long time.

“We’ve lost about 300,000 jobs already, and more than a million Londoners are currently furloughed,” said Mayor Sadiq Khan, who is seeking re-election. “So the challenge is how we avoid (the) mass unemployment of the 1980s.

“It’s really important to have the same ambition that our forefathers and foremothers had after the Second World War, because that’s scale of the challenge,” said Khan, whose priorities include coaxing people back into the city center and easing the economic inequalities exacerbated by the pandemic.

If opinion polls are right, Khan, 50, is likely to win a second term in Thursday’s election, which has been delayed a year because of the pandemic. Both he and his main challenger are made-in-London success stories.

Khan, a lawyer and member of the center-left Labour Party, is the son of Pakistani immigrants. His father was a bus driver, his mother a seamstress.

Conservative candidate Shaun Bailey’s grandparents, meanwhile, are part of the “Windrush generation” of post-World War II immigrants to Britain from the Caribbean. He was raised by a single mother in public housing in Ladbroke Grove, an area where pricey Victorian houses sit near run-down social housing blocks.

The 49-year-old former youth worker is a passionate advocate of the city that he says gave him chances to thrive.

“More than any other place in the world, if you come from a working-class background, London offers opportunities like no other,” said Bailey, who believes London’s biggest challenge is crime.

Bailey wants to see more youth workers, more police officers on the beat and greater use of stop-and-search powers to take knives and other weapons off the street. Stop-and-search is a hugely contentious policy because young Black men have been disproportionately targeted but Bailey says it’s essential.

“The thing that’s making the Black community angry above all things is the rate at which our young people are dying,” he said.

Both Khan and Bailey — and more than a dozen other candidates, from Liberal Democrat and Green contenders to anti-lockdown activists, YouTube prankster Niko Omilana and a bucket-headed comedian called Count Binface — know they are running in a city transformed by the virus and by Britain’s exit from the now 27-nation European Union.

Brexit poses a challenge to London by ending the free flow of people from the continent and imperiling the city’s status as Europe’s financial hub. The pandemic has challenged the very existence of megacities and the crowded spaces in which people live, work and travel.

After three decades of growth, London’s population fell in 2020 as people moved out in search of more space during lockdown or returned to their regions or home countries. It remains to be seen whether they will ever come back.

Three lockdowns, now gradually being lifted, kept office workers at home and turned central London into a ghost town. Millions no longer commute downtown to work or play, as coronavirus restrictions forced people to stay local.

Across London — a “city of villages” whose neighborhoods retain distinct characters — the pandemic has led people to reassess their priorities.

“If you go into central London … there’s nobody there, almost,” said Mark Burton, who runs a community arts venue in Walthamstow, a once-gritty, now-gentrifying area in the city’s northeast. “Whereas out here, there’s a vibrancy around the cafes.”

Burton thinks Khan has done a pretty good job as mayor, though he wants more support for cycling and community ventures.

Across town in Ladbroke Grove, Nicholas Olajide likes Bailey’s pledge to cut crime. He, too, thinks the pandemic has given the city a new sense of itself.

“I think it has awakened a sense of community in people,” Olajide said. “Before, London was going the way whereby we were no longer a community, no longer our neighbors’ keeper. But I think that has brought us back together. People staying home and caring about their neighbors, working from home — it has brought families closer together.”

Sian Berry, the Green Party candidate for mayor, says the pandemic has exposed the yawning gaps in London society and left people wanting “a new start.”

“It’s a very exciting place to live, London, but it’s polluted, it can be a strain, and living costs are far too high,” she said. “Each neighborhood in London has its own spirit, too, and we need to be nurturing that.”

Brown, the historian, is optimistic about London’s ability to bounce back, noting that it has been through tough times before in its 2,000 years of existence.

“London’s ancient history really is one of getting set on fire every now and then — the whole city burns down — and then everybody gets the plague,” he said. “This happens in a cycle for years and years and people keep coming back.

“The very long history of London is one of incredible resilience. It’s even a little uncaring sometimes. It doesn’t always take everyone with it. But the place itself, its economy, its appeal, kind of endures,” he said.

___

Associated Press Writer Danica Kirka contributed to this story.

___

Read other installments in the AP’s “London: Beyond the Pandemic” series: https://apnews.com/article/london-beyond-the-pandemic-837183578755

Copyright © 2021 . All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.