Temperatures were boiling almost every where in the U.S. last week, breaking records in the Pacific Northwest and sparking fresh conversations about climate change.

While it may have cooled off on the East Coast, climate change talk is heating up. It’s even entered the realm of your 401(k), and the agency that manages the Thrift Savings Plan has fielded a growing number of concerns about the financial risks of climate change in the last year.

House and Senate Democrats have legislation that would create a new advisory panel inside the Federal Retirement Thrift Investment Board, which would study the financial risks of climate change on employee benefits.

The Restructuring Environmentally Sound Pensions In Order to Negate Disaster (RESPOND) Act — yup, it’s a mouthful! — requires the TSP to divest from fossil fuel companies if the new advisory panel decides it makes sense. If it doesn’t, the bill calls on the plan to create a “climate choice” investment option.

The FRTIB has some problems with this bill, but we’ll get to those later.

Then, there’s a recent executive order from the Biden administration, which directed the Labor Department to “protect the life savings and pensions” of U.S. workers, including federal employees, from climate-related financial risks.

Labor and the White House will examine how the FRTIB has taken environmental and climate-related financial risks into account. A report on their findings is due to the president within the next few months.

The Government Accountability Office recently added its own concerns to the mix. It spoke with environmental experts and officials from the United Kingdom, Japan, Sweden and other countries that have taken steps to incorporate climate change risks into their public sector retirement plans.

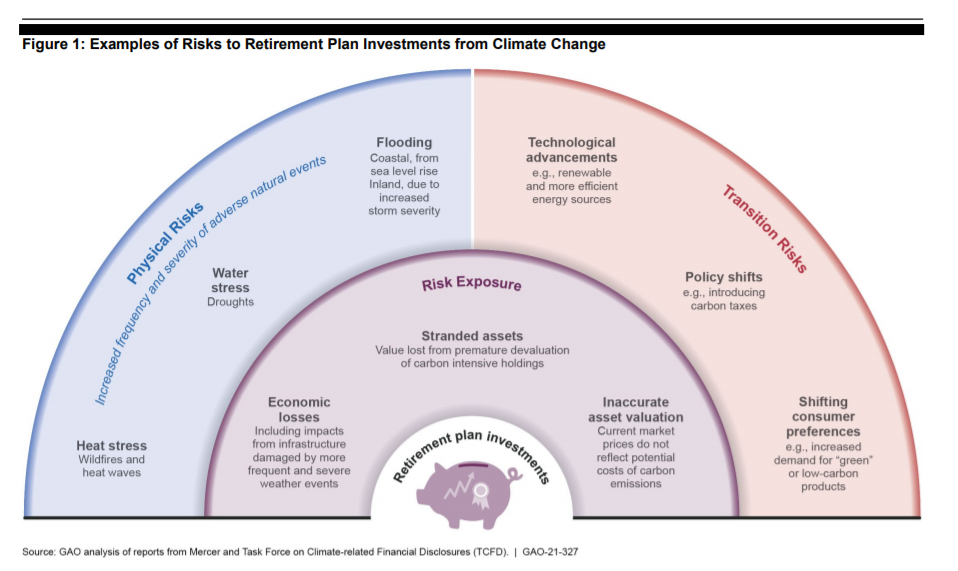

Climate change and natural disasters pose “widespread economic impacts,” which in turn trickle down to federal employees, retirees and their investments. GAO has a handy illustration that shows how more intense heat, storms and droughts may trigger economic losses, policy and technology changes and even potential shifts in consumer preferences or practices.

All of these events could mean new things for, say, the gas company you’re partially invested in.

The FRTIB, GAO said, hasn’t assessed these risks and their effects on the TSP and its investments.

Now here’s where it gets complicated.

The FRTIB disagreed with GAO’s characterization that it “does not currently have any knowledge” of climate change risks. The agency follows the conversations and is well aware of the policy debate, FRTIB Executive Director Ravi Deo said in response to GAO.

The TSP uses a strict indexing discipline with a broad set of market opportunities. Risk in one sector shouldn’t necessarily translate into risk for all, the FRTIB said.

“While some firms will lose value due to climate change, others will gain; climate change does not necessarily portend universal downward risk,” Deo wrote.

The FRTIB subscribes to the efficient market theory, where if there’s risk from climate change, for example, investors will already be aware of it and stock prices would reflect that risk. In addition, the board uses a passive investment strategy and doesn’t focus on specific risks to a particular industry or company.

The board and the TSP, by law, are supposed to act in the sole fiduciary interests of their participants, all 6.2 million of them.

It’s why the board wanted to push ahead last year with plans to move the international fund to a new, China-inclusive benchmark. The move would have given TSP participants access to large, mid and small-cap stocks from more than 6,000 companies in 22 developed and 26 emerging markets. An independent consultant said it would have improved the anticipated returns for TSP participants.

Plans to adopt the China-inclusive index have been indefinitely on hold for the last year amid pushback from the Trump administration and a bipartisan group of senators, who didn’t think it was appropriate for federal employees and military members to invest in an adversary.

Yes, the TSP-climate change debate is different than last year’s back-and-forth over the I fund.

But ultimately, the TSP has similar concerns. The FRTIB isn’t a policy agency, and participants’ fiduciary interests must drive all decision-making at the board.

The RESPOND Act contemplates a scenario where the TSP can divest from all fossil fuel companies. But doing so would effectively drain four of the plan’s funds, the agency has said. The C fund, for example, is based on the S&P 500 index. There’s no practical way at the moment for TSP participants to invest in any other company on the S&P 500 that isn’t a fossil fuel company.

Creating a “climate choice” fund would overlap with other TSP funds as well, the FRTIB has said.

So what’s next? The TSP said it acknowledges some participants want the option of investing in other funds beside the plan’s core five. It will offer a mutual fund window next summer, giving participants a chance to take a portion of their TSP accounts and invest in an array of mutual funds on a platform offered by a TSP vendor.

In the meantime, a consultant will also conduct its next investment review in fiscal 2022, the FRTIB told GAO. The board has said it will work with the Labor Department on the White House-directed review of climate-related financial risks.

But no, the TSP climate change debate isn’t over.

Nearly Useless Factoid

By Alazar Moges

The most dangerous ant in the world is the bulldog ant found in coastal regions in Australia. In attack it uses its sting and jaws simultaneously. There have been at least three human fatalities since 1936, the latest a Victorian farmer in 1988.

Source: Guinness World Records