FLAGSTAFF, Ariz. (AP) — For Native Americans, Deb Haaland is more than an elected official on track to become the first Indigenous secretary of the Interior Department. She is a sister, an auntie and a fierce pueblo woman whose political stances have been molded by her upbringing.

News of her historic nomination electrified Indian Country. Tribal leaders and organizations for weeks have urged people to write and call U.S. senators who will decide if she’ll lead the agency that has broad oversight over Native American affairs and energy development.

On Tuesday, Haaland’s confirmation hearing will be closely watched in tribal communities across the U.S., with virtual parties amid a pandemic. A day before, a picture of the New Mexico congresswoman was projected on the side of the Interior building with text that read “Our Ancestors’ Dreams Come True.”

Many Native Americans see Haaland as a reflection of themselves, someone who will elevate their voices and protect the environment and tribes’ rights. Here are stories of her impact:

________

ALETA ‘TWEETY’ SUAZO, 66, LAGUNA AND ACOMA PUEBLOS IN NEW MEXICO

Suazo first met Haaland when they were campaigning for Barack Obama, walking door to door in New Mexico’s pueblos.

When Haaland herself was chosen to represent New Mexico as one of the first two Native American women ever elected to Congress, she turned to Suazo and the state’s Native American Democratic Caucus to make treats to hand out for a reception.

They made hundreds of pueblo pies, or pastelitos, and cookies, froze them and took them to Washington, D.C. Wearing traditional black dresses, they handed out the goodies with a thank-you note from Haaland.

Suazo said she admired Haaland because she is eloquent and smart, “no beating around the bush,” and she is a member of Laguna Pueblo who has returned there to dance as a form of prayer.

When she heard Haaland was nominated as Interior secretary shortly after winning a second term in Congress, Suazo wasn’t overjoyed.

“Oh my gosh, she is going to go there, and who is going to represent us?” said Suazo, who lives in Rio Rancho, New Mexico. “Who is going to represent New Mexico? There goes our one and only Indian representative.”

She wanted to be assured that Haaland would be replaced by someone just as dynamic, who would work hard to protect the environment, address an epidemic of missing and slain Indigenous women and expand broadband, she said.

“I was happy, but I was afraid. I didn’t want to lose her,” Suazo said.

But she sees the significance and importance, she said, in having a Native American oversee an agency that touches nearly every aspect of Native American life. Suazo said she’ll be watching, ready to yell at the screen if anyone questions Haaland’s qualifications.

And to Haaland, she sends the message: Gumeh, or be a strong woman.

____

BRANDI LIBERTY, 41, IOWA TRIBE OF KANSAS AND NEBRASKA

When Liberty saw a picture of Haaland in a traditional ribbon skirt and moccasins for Joe Biden’s inauguration, she cried.

She thought about her grandmother Ethil Simmonds Liberty, who didn’t become a U.S. citizen until she was 9 despite being born in the U.S. on her tribe’s reservation that straddles Kansas and Nebraska. Her grandmother was a powerful advocate for her people, petitioning to turn a pigpen into a playground, writing letters to U.S. presidents and leading the way to get a road paved to the reservation, she said.

Brandi Liberty thought about her own daughter, who she is hopeful will carry on her legacy in working with tribes and embracing their heritage.

She thought about her time in college earning a master’s degree and seeing single mothers bring their children to class, each of them understanding that it wasn’t a burden but a necessity. She later became a single mother like Haaland, who has often spoken about the experience, relying on food stamps and amassing debt working through college.

Liberty also thought about other tribal nations and what Haaland could do in terms of moving them in the right direction and connecting them to Washington, D.C. Essentially, Liberty’s grandmother on a larger scale.

“This is no different than when Obama became the first Black president and what that signified,” said Liberty, who lives in New Orleans. “This is a historical mark for Indian Country as a whole.”

____

ZACHARIAH RIDES AT THE DOOR, 21, BLACKFEET TRIBE OF MONTANA

Rides At The Door is studying environmental sciences and sustainability, and fire science as a third-year student at the University of Montana in Missoula.

He brings a perspective to his studies that Haaland has been touting as unique from Indian Country — that everything is alive and should be treated with respect and that people should be stewards of the land, rather than have dominion over it.

In high school, he learned about the mining industry and how it has impacted sites that are part of the Blackfeet creation story. He learned about the stances the American Indian Movement has taken to fight for equality and recognition of tribal sovereignty. He’s also recently learned that the United States had a Native American vice president from 1929 to 1933, Charles Curtis.

Seeing Haaland’s political rise is inspiring, he said.

“It’s a great way for younger Natives to say, ‘Alright, our foot is in the door. There’s a chance we could get higher positions,’” he said.

He’s not yet certain what he wants to do when he’s done with college. But he knows he wants to learn the Blackfeet language, and maybe become a firefighter or work on projects that route buffalo to the Blackfeet Reservation.

He plans to catch at least part of Haaland’s confirmation hearing from home, hopeful she’s successful and can challenge Western ideology.

___

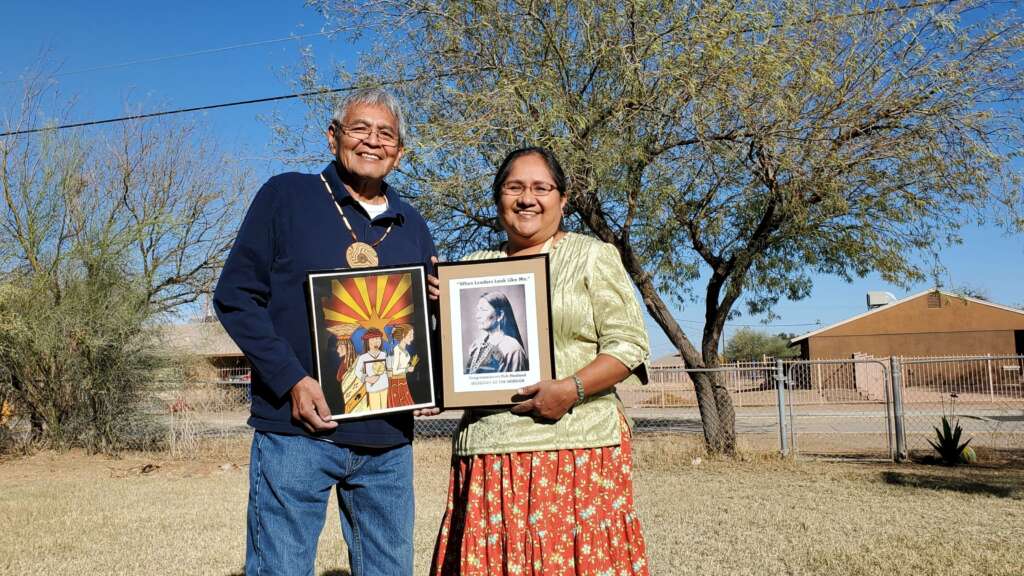

DEBBIE NEZ-MANUEL, 49, NAVAJO NATION IN ARIZONA, NEW MEXICO AND UTAH

During her recent campaign for an Arizona legislative seat, Nez-Manuel sought an endorsement from Haaland. She was looking for someone whose values aligned with hers: grounded in beliefs, connected to the land, a consistent and strong leader unchanged by politics.

After layers of vetting, she got the endorsement and planned to announce it at a get-out-the-vote rally at the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona, featuring Haaland. It also was a chance for the two women to take a picture together.

Then, the event was canceled because of the coronavirus pandemic. Nez-Manuel was devastated.

Days before she was supposed to meet Haaland, Nez-Manuel was sitting at home when her phone rang. She didn’t recognize the number but answered anyway.

“Hey Debbie, this is Deb,” the voice on the phone said.

“Who?” Nez-Manuel asked.

The caller replied: “Deb Haaland. Good morning. I’m calling from New Mexico. I’m sitting in my kitchen.”

Nez-Manuel’s heart was racing, and she struggled to put all her thoughts she had so carefully scripted for that meeting into words. Haaland, she said, was patient and shared stories about life on and off a reservation — something that resonated with Nez-Manuel — and reaffirmed that Haaland hasn’t forgotten her roots.

“It’s like talking to an auntie,” she said. “She’s very matter of fact.”

Nez-Manuel joked about getting a plane ticket to watch Haaland’s confirmation hearing in person to get that elusive picture.

Instead, she and her husband, Royce, will be watching from home on the Salt-River Pima Maricopa Community northeast of Phoenix. They’ve encouraged their children’s teachers to incorporate the hearing into lesson plans and tribes to help answer questions about the process.

Copyright © 2021 . All rights reserved. This website is not intended for users located within the European Economic Area.